Two Images

- Vidura Bahadur

- Sep 29, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Oct 2, 2020

In this essay Vidura Jang Bahadur traces the provenance of two photographs made five decades apart.

Photograph by Kulwant Rai/ Photo courtesy Aditya Arya

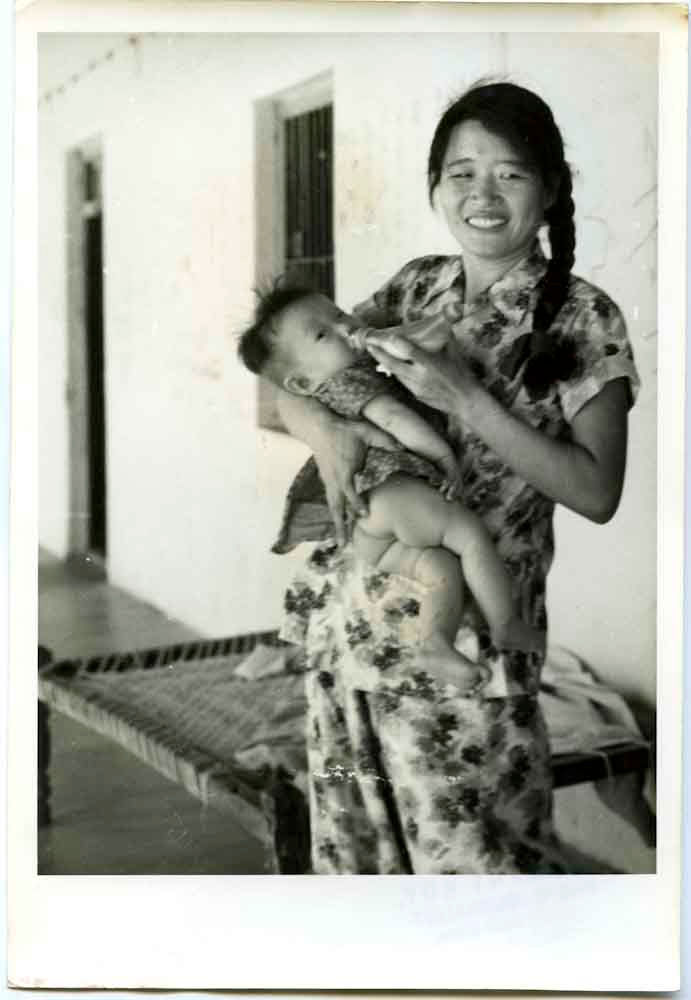

The image, a scanned copy of an old photograph, yellow around the edges, shows a woman, possibly in her twenties or early thirties, holding a small child in her right arm as she tries to feed the child milk with an oddly shaped bottle in her left. She is smiling and looks away from the camera. The baby, head turned, looks directly at the camera. There is a charpai (a traditional Indian woven bed) behind her and one can see a window with a metal grille and a door in the background. The woman in the photograph wears a floral dress similar to what many Chinese women wear at home. The ease with which the woman stands, the casual nature of her dress and the charpai give the impression that this is a domestic setting or an environment that the subject of the photograph is familiar with. Her gaze away from the camera indicates shyness on her part or hints at the possibility that the woman in the picture does not know the photographer. This would be difficult to say with certainty if I came across the image in a family album. The photograph could have been made anywhere, if it were not for the charpai that gives the image a distinctly Indian flavor. From looking at the photograph itself, it is difficult to say it was made in an internment camp in Rajasthan, India.

A scan of the back of the photograph shows a caption that states at the top “DEOLI CAMP FOR CHINESE INTERNEES”. Below that it says, “A happy Chinese mother and child at the Deoli camp. For children under 5, there is an extra ration of a half litre of tested and pure milk a day”. The caption, faded with age, is typewritten on a brown piece of paper stuck to the back of the photograph. The scan does not show the entire back of the photograph but just a little more than the brown cover paper with the caption on it. On the edges of the scan I can see traces of two stamps, Y and ST, and another stamp that says ‘from’ and then below that the letters ‘gover’.Iinferthatitmaystand for government, given the nature of the caption itself, and how the caption is pasted and stamped, but I cannot say for sure.

The photographs of the camp, made by Kulwant Roy, a photographer active in post independence India, survive thanks to the effort of the India Photo Archive that houses his work. I came across the archive thanks to Roy’s nephew, Aditya Arya, a photographer and archivist. He had walked up to me after a presentation I had made of my work on the Chinese in August 2009 saying that in his uncle’s archives was set of negatives described briefly as Chinese in Rajasthan. Till then he had never known the context for the images. It’s difficult to ascertain if any of the images that Roy made of the camp were published in the 1960s, but they are among the very few images that survive of what is a largely unacknowledged part of Indian history.

In 1962, during the border conflict between India and China, many Chinese, some of whom had been living in India for several generations, were interned in a camp in Deoli, Rajasthan. In her memoir, Doing Time with Nehru, Yin Marsh, a writer and former internee of the camp in Deoli, describes the ordeal of being a Chinese Indian living in India during the time of the war from the perspective of a young girl. She was thirteen at the time. In a conversation over email she said, “I felt somehow ashamed of what happened to us, as though we had done something wrong. I was born in India and felt I was Indian. I could never understand why we were singled out. We were civilians, just living our lives like everyone else. For my part, and I think I can speak for others too, we were totally humiliated and our lives as we knew them were destroyed. Once we embarked on a differentpathtoadifferentlife,we wanted to leave that sad part of our livesbehind.”

Marsh adds that once the internees were finally released they were not allowed to return to the places they had lived in before. During their time away in the internment camps, the government had seized their properties and auctioned them. There was little to go back to. Travel between cities was restricted for Chinese Indians, as they needed permits to travel from one place to another. Life was hard for the community and those who could leave left for Canada and other parts of the world to start afresh.

My interest in the community was sparked by a visit to Kolkata to witness the Chinese New Year in early 2003. Tangra, the suburb of Kolkata where large majorities of the city’s Chinese community reside, was far from what I had imagined. There were restaurants and little family eateries jostling for space with the tanneries and sauce factories. The lines between home and workspaces were all blurred. Keen to document the lives of the community in Kolkata I spoke to a friend’s uncle. Shrugging his shoulders, he simply said, “what is there left to document, and why?” What he said still remains with me. I don’t think I truly understood the meaning of this sentiment then but over time as I came to know more about the community’s history in India I began to understand better why he felt that way.

It was only several months later after my visit to Kolkata that I learnt of the internment of Chinese families in Deoli, although few spoke about the camp and the persecution that they experienced at the hands of the authorities. They feared that they would be interned once more or asked to leave India in the instance of another war between China and India. This fear pushed the community towards silence.

Following a mention in an essay on the Chinese Indian community by writer Dilip D’Souza, I traveled to Tinsukia, a small town in Assam, in December 2013. Tinsukia and the neighbouring town of Makam had been home to many Chinese before the war in 1962. Now only a few families remained. John Wang, who now runs a Chinese restaurant called Hong Kong, was among those that D’Souza interviewed for his essay and whose family had been interned in the camp.

I remember the day I met Wang and his mother, Li Su Chin, now in her late eighties, at their restaurant- cum-residence in Tinsukia. There was a bandh (curfew) and the streets were largely deserted except for the presence of military vehicles and Indian army soldiers patrolling the streets. I entered through a door that led to a courtyard and then into the restaurant through a side door. The restaurant was dark, the windows closed because of the bandh. I was seated on a stool near the cashier’s table, a plain wooden desk in the middle of the small room that lay between the house and the other rooms that made up the restaurant.

Wang arrived shortly and took his place behind the desk, looking through the drawers and leafing through papers on the desk. Even though the bandh was in place there remained business to attend to. In time his mother walked in and he dutifully vacated his seat behind the table for her. A policeman walked in asking if it was possible for them to rustle up a bowl of noodles. Wang’s mother, quiet and attentive, asked a helper standing by her side to place an order and asked the policeman to sit at a table in the restaurant. This seemed a common occurrence and over the afternoon there were other regulars who stopped by to see if they could cook a plate of momos or chow mein.

I was struck by the ease with which she communicated with both customers and workers at the restaurant. She spoke little and communicated largely with just a shake of her head or hands. The workers in the restaurant knew exactly what she wanted and went about doing her bidding without asking questions. Even though Wang ran the kitchen and did the daily shopping, it was his mother who sat at the desk, approved the policeman’s request for a plate of noodles during a curfew, received and doled out money. At 86, she was still in control of the family business.

We spoke briefly, Wang repeating what I already knew about the family from D’Souza’s essay. Before the war in 1962 Wang’s father, Wang Shu Chin, ran a successful sawmill in Tinsukia supplying sleepers to the Indian Railways. During the war they lost everything, the GMC vehicles and the many elephants they owned, the machinery in the sawmill and all their other property was seized and sold by the government. His father, he remembers, turned to providing private tuition and survived the years after the war with the help of other families. In 1970, they opened the restaurant. I sat with Wang and his mother for a few hours and before leaving made a few photographs of him, his mother and other members of the family.

It was in the summer of 2015 that I finally made time to head back to Tinsukia, stopping for a day to meet Eugene Tham, a prominent member of the Chinese Indian community in Guwahati, Assam. I had landed in Assam at a time when residents of the state were being asked to submit evidence that they or their ancestors were residents of the state as part of an initiative to update the National Register of Citizens (NRC) of 1951. The mention of individuals in the electoral rolls of 1971, or other admissible documents that proved their presence in the state before March 1971, was taken to be legitimate proof of their citizenship.

I met Eugene at his home, where over a cup of tea we looked though old family albums talking about his late father and other Chinese families in Assam. I asked Eugene about the NRC and whether it had affected any of the Chinese families that lived in the state. He replied in the negative adding that some of the Chinese had even used their release letters from Nagaon (previously Nowgong) jail to prove their residency in Assam. I smiled. The irony that members of a once ostracized community could use evidence of their internment to prove their citizenship to the same state was hard to miss. With this, the conversation turned to the war and the internment of the Chinese in Rajasthan. I was sharing stories of the many people I had met during my travels who were interned in Deoli when I remembered the photographs that Aditya Arya had shared with me. Taking out my phone I showed Eugene the few photographs of the camp that Kulwant Roy had made during his visit to Deoli. He looked through the images, pausing only when he saw the image of the woman and child that I described at the beginning of this essay. He called his mother to confirm the identity of the woman in the image. After a brief discussion he turned to me and said, “ask John Wang, it could be his mother”.

Li Su Chin, Tinsukia

I carried a print of a portrait I had made of Wang’s mother as I walked the streets of Tinsukia towards Cheena Patty where Wang’s family- run Hong Kong restaurant is located. It shows Wang’s mother seated at the cashier’s table. There is an uneasy stillness to the image, conveyed by the expression on Wang’s mother’s face. It’s difficult to tell what she’s thinking even though she appears calm and possibly in a reflective mood. She’s looking down and I wonder if she’s just waiting for me to make a photograph and leave, or if she’s thinking about another time, person or place. Or is she simply waiting for the next customer to step in and to start the process of taking orders once again? A ritual that brings much comfort and order to her daily life. It is difficult to tell. Her left arm is placed over her right, as if a defence between the photographer and her thoughts. On the left of the table is a fridge with the Coca Cola insignia and on the wall behind it a photograph of Wang’s late father Wang Shu Chin garlanded with plastic flowers. It’s the kind of photograph that people put up in their homes to remember their loved ones; he looks directly at the camera. It’s not a remarkable photograph but there is a quiet warmth to it. This is in sharp contrast to my image of Wang’s mother seated at the table. Beside that, on the right, is a sign for ‘no credit,’ a common sight in many shops in the area, although allowing people to pay in kind or later is not uncommon in practice. The room is lit by a strip of fluorescent lights not visible in the frame, which registers as greenish on the daylight- balanced film that I use. It is possible that it is this quality of light, and the solitary central figure surrounded by an inanimate assortment of objects, that makes me uncomfortable. It’s as if all life has been drained from the world in front of me.

On hearing from a waiter that I’m in the restaurant, Wang appears shortly. The family is eating lunch in a room directly behind the room with the cashier’s table. Wang disappears behind the curtains with the portraits that I have made of his mother and other members of the family. I wait for him to return, eager to speak to him about the photographs from the camps. In time Wang returns and we start talking. He asks me to stay for lunch and once he places an order for noodles I show Wang the scans on my phone. He’s surprised. Very few photographs of the camps exist. “Yeh to mummy hai, hum poochta hai!” he exclaims, confirming it is his mother before disappearing behind the curtains to show the photograph to her. I hear some surprised noises from inside. I edge closer to the curtain and see Wang’s mother and other members of the family seated around a long table. Wang is showing the scanned images on my phone to everyone around the table. Wang turns to me and reaffirms that it is his mother.

I ask him about the baby in the photograph. I scan the faces of people in the room and wonder which one of them their mother is holding in her arms. Wang’s mother is seated at the far end of the table and shows little interest in the images, now apparently absorbed once again by the food in front of her. Wang turns to me and tells me that the child in the photograph is the sister they lost to chickenpox a year after reaching Rajasthan. There’s a mention of this incident in the essay by D’Souza. In the essay Wang says that his sister had fever for three days and “her skin turned black, and there was no doctor service.” Others who lived in the camp had also mentioned such instances to me. I had hoped that the response to the photograph would have been different, somehow joyful. That Wang or his mother would point to another person sitting on the table or mention another sibling in another part of the world, or that possibly the photograph would bring back a memory from the camp or spark a conversation about the child in the picture. I look at Wang’s mother. She remains quiet.

In his essay D’Souza describes a scene where he is sitting with Wang at the restaurant talking about his years in the camp when his mother walks into the restaurant. Hearing Wang talk about the camp she whispers to him in Hindi, but loud enough for D’Souza to hear, that he should not talk about these things. “They are finished now.”

Close to five decades have passed since the war, between when the two photographs were made, the first in the camp in the 1960s and the second more recently in 2013. Much has changed.

Komentarze